Introduction

If you zoom out far enough on a chart of a major stock market index—like the S&P 500 or India’s Sensex—over many decades, the overarching trend is undeniably upward. This long-term ascent is a powerful testament to human ingenuity, economic growth, and the wealth-generating capacity of well-run businesses. It’s this very chart that depicts a beacon of hope for future prosperity and draws many of us to investing.

The question then arises is- If stock markets are tied to economic growth, innovation, and the success of companies, then why don’t they always rise? If population grows, businesses expand, and technology improves, shouldn’t the market should go up all the time?

This is a question that every beginner thinks about at some point. Why there are unnerving drops, the stagnant periods, the gut-wrenching crashes that interrupt the otherwise optimistic upward trajectory time to time? Why do we see bear markets, corrections, and downturns that can last for months or even years?

So let’s take a moment to think through this together. Why doesn’t the stock market just go up in a straight line?

Stock Markets Reflect Expectations, Not Just Reality

One of the core principles to understand is that stock prices are not just based on what is happening now, but on what people think will happen in the future. If investors think the future will be better, prices go up. If they think it will be worse, prices fall.

Often times the future expectations are already priced into many stocks.

Let’s say a company made $1 billion in profits this year. That sounds good. But if analysts expected $1.5 billion, the share price might still fall. Why? Because the market probably had already "priced in" those higher expectations. Stocks are often a story about the future. And when the story changes, so does the price.

Infact stock markets actually often act as a leading indicator of upcoming economic trends, meaning they tend to fall before a recession is officially declared and can start to rise before the economic recovery is obvious to everyone.

This anticipatory nature means the market isn't just reacting to "current" conditions but also to expectations of future economic health. If those expectations sour, even in a currently decent economy, the market can falter.

Short-Term Emotions vs. Long-Term Growth

In the long run, stock markets generally rise. Historically, markets have trended upward over decades in most nations. Though exceptions exist, like Japan's lost decade.

But in the short term, human emotions take the driver’s seat. Fear, greed, panic, and overexcitement can all cause wild swings either way.

Even a whisper of bad news can lead to a sell-off, and an overly optimistic rumour can inflate prices irrationally. These swings are not always rational.

"The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent." - John Maynard Keynes

The above quote speaks volumes about the powerful role human psychology plays in market movements. Many of us are not perfectly rational calculating machines; particularly in stock markets we are driven by emotions of greed and fear.

- Greed: When markets are rising strongly, greed often takes over. Many people see others making money and jump in, often with little regard for valuation, simply because they don't want to miss out on the perceived easy gains. This fuels further price increases, creating a positive "feedback loop" that can lead to bubbles.

- Fear & Panic Selling: Conversely, when markets turn down, fear becomes the dominant emotion. The fear of further losses can lead to panic selling, as investors rush for the exits simultaneously. This collective selling pressure can drive prices far below their intrinsic values, creating opportunities for those who can keep their cool.

- Herd Behavior: Many people have a natural tendency to follow the crowd. In investing, this means buying when everyone else is buying and selling when everyone else is selling. This amplifies market swings, pushing prices further from their fundamental anchors in both directions.

The stock market is thus a vibrant, sometimes erratic, dance between tangible economic realities and the intangible spectrum of human emotions.

So while the long-term trend is still powered by economic growth and innovation, but that path is paved with cycles, corrections, and the occasional crisis because in the short run it reacts to headlines, tweets, elections, interest rate talks, wars, or even weather. The collective mood swings of many market participants reacting to such news in their own ways, from euphoria to despair, are a primary reason why share prices don't follow a smooth path.

The Unforgiving Gravity of Valuation

"Price is what you pay; value is what you get"- Warren Buffett.

While corporate earnings and economic growth can provide the fuel for rising stock prices, these prices cannot become completely untethered from their underlying fundamental value indefinitely.

Sometimes the market goes up too fast especially when there is a lot of euphoria. Many traders discard valuations and start believing that prices will keep rising forever. This creates bubbles— when share prices become much higher than the actual value of the companies and years of futures are already priced in.

But bubbles eventually burst. All it requires is just one misstep in those future expectations. When reality hits or expectations are not met, a correction happens.

Thus overvalued markets are always fragile. A disappointing earnings report, a shift in sentiment, or an external shock can break this fragility.

Prices then correct—sometimes gradually, but often sharply—falling back towards (or even below) their intrinsic values.

Such kind of corrections (due to overvaluations) aren't indicative of something bad in the economy. But rather the market is self-correcting from a period of irrational exuberance. An investor should see this not as a disaster, but as the market returning to its senses.

The Economic Engine and Its Cycles

At its heart, the stock market is a reflection (albeit sometimes a distorted one) of the underlying economy. Economies are not static; they breathe. They go through natural cycles of expansion, peak, contraction (recession), and trough, before embarking on a new expansion.

- Expansion: During periods of economic growth, businesses typically thrive. Employment is high, consumer spending is robust, corporate profits increase, and investor optimism tends to push stock prices up.

- Peak: Growth eventually moderates. The economy might be running at full capacity, inflation could be picking up, or certain sectors might become overheated.

- Contraction (Recession): If imbalances become too great or shocks occur, the economy can contract. Businesses might cut back on investment and hiring, consumer spending often declines, profits shrink, and fear can drive stock prices down significantly.

- Trough: Eventually, the excesses are worked out, government and central bank interventions might take effect, and the stage is set for recovery.

Stock markets often rise during booms and fall during busts. That’s why we see periods of bull markets (rising prices) and bear markets (falling prices). These are natural parts of the economic cycle. Just like no season lasts forever, no economic condition does either. Spring is followed by summer, but winter eventually comes too. Markets rise and fall accordingly.

The Reality of Business: Not All Companies Succeed Indefinitely

While the overall market might trend upwards due to innovation and broad economic growth, individual companies and even entire industries can face challenges that cause their stock prices to decline, sometimes permanently.

During the times of uncertainties, small cap companies are often hit harder than large caps. This is because they typically have less access to capital and fewer resources to weather economic storms. Additionally, their business models may be less diversified, making them more vulnerable to specific industry challenges.

For instance, this was the case in India before the covid pandemic (2018-19) when the small and mid cap companies faced a lot of downturns yet the nifty 50 index was still rising.

Besides many companies are themselves cyclical in nature. For example, the steel industry is often tied to construction and infrastructure spending. The aluminium industry is often tied to the automobile and electronics sectors. If these sectors face downturns, the companies within them may struggle, even if the overall market remains strong.

The stock market is a dynamic collection of many of these individual stories. When we say "the market is down," it doesn't mean every company is falling. It just means that, on average, the index (like the S&P 500 or Sensex) is falling. Within that, some companies might still be doing well. This diversity is what makes investing both challenging and rewarding.

The Interest Rate Compass and Monetary Policy

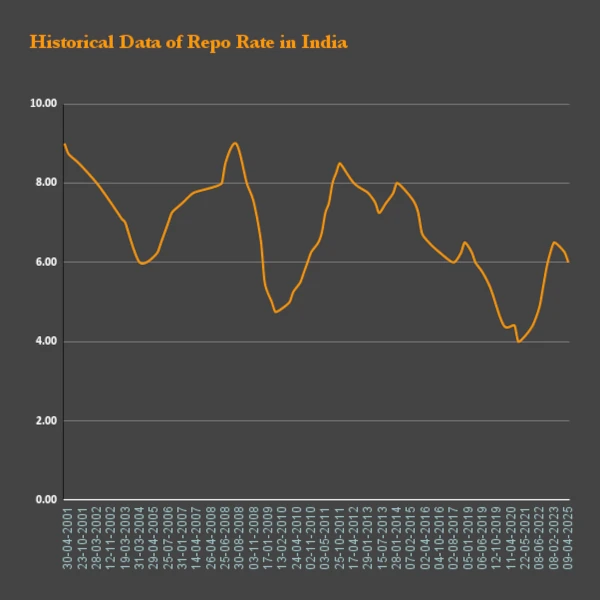

Central banks, like the Federal Reserve in the U.S. or the Reserve Bank of India, play a significant role in the economy through monetary policy, primarily by influencing interest rates and the money supply.

- Rising Interest Rates: When central banks raise interest rates (often to combat inflation), borrowing becomes more expensive for businesses and consumers. This can slow down economic growth and reduce corporate profitability. Higher interest rates also make lower-risk investments like bonds relatively more attractive compared to stocks, potentially drawing capital away from the equity market.

- Falling Interest Rates/Quantitative Easing: Conversely, lowering interest rates or injecting liquidity into the system (quantitative easing) can stimulate borrowing and investment, potentially boosting economic activity and stock prices.

Shifts in monetary policy, or even just expectations of such shifts, can cause unexpected reactions from market participants

External Shocks and Geopolitical Tremors

The world is an unpredictable place. Unforeseen events can send shockwaves through financial markets, regardless of the underlying economic fundamentals or valuations.

- Pandemics: As we saw with COVID-19, global health crises can shut down economies and create massive uncertainty.

- Wars and Geopolitical Conflicts: Conflicts can disrupt supply chains, impact commodity prices, and create widespread investor anxiety.

- Natural Disasters: Large-scale disasters can have significant economic consequences for affected regions and industries.

- Trade Disputes and Policy Changes: Unexpected shifts in government policy or international trade relations can unsettle markets.

While markets often recover from such shocks over time, their immediate impact can be sharp and severe, leading to significant downturns. These rare, unpredictable events are often called "black swan" events. They remind us that uncertainty is always part of investing.

Conclusion

Stock markets don’t always rise because they are reflections of a complicated world, constantly reacting to what is known, what is guessed, and what is feared. They reflect not just present realities, but future expectations, human emotions, economic cycles, and external shocks.

Understanding why markets fall is not about predicting the next crash. It’s about understanding that volatility is not your enemy. It is part of the deal of being in equity markets.

In bear markets, it's precisely these periods of irrational pessimism, overreaction to bad news, or cyclical downturns that create the discrepancies between market price and intrinsic value—the very discrepancies a value investor seeks to exploit.

Happy investing!

Comments